The formal test programme begins this week on the technologies required to detect gravitational waves in space.

Europe’s Lisa Pathfinder probe will engage in a series of experiments roughly 1.5 million km from Earth.

The project has heightened interest, of course, because of the first sampling of the ‘cosmic ripples’ made by ground-based detectors last September

A successful demo for LPF would pave the way for a fully operational orbiting observatory in the 2030s.

This would likely be known simply as Lisa – the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna.

‘It’s a wonderful time right now,’ said Paul McNamara, the European Space Agency’s project scientist on Lisa Pathfinder.

‘I’ve spent my entire career in this endeavour, and for years we were told – even ridiculed in some cases – that gravitational waves don’t exist, or that we’d never find them.

‘Well, now we have found them, and we’re about to take the next big, big step towards building a mission that could detect them in space,’ he told BBC News.

The Earth-bound laser interferometers sited at the Advanced Ligo facilities in the US are sensitive to the gravitational waves generated in ‘smaller’ cosmic events.

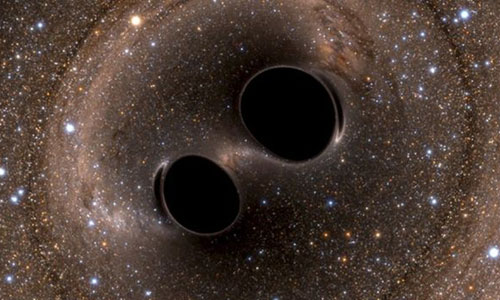

Back in September, they observed the signal produced at the moment two black holes, each about 30 times the mass of our Sun, whirled around one another and merged.

A space-based laser interferometer would chase much more massive targets – the monster black holes, millions of times the mass of our Sun, that coalesce when galaxies collide, for example.

It is possible, however, that an orbiting observatory might also see Ligo’s lesser events – just at a different stage of their evolution.

One back-of-the-envelope calculation has suggested a fully operational Lisa mission could have witnessed Ligo’s in-spiralling black holes four years ago – had the mission been flying back then. This is when the frequency of the gravitational wave signal emanating from the dancing holes would have crossed the sensitivity range of a space interferometer.

Lisa Pathfinder contains just the one instrument, which is designed to measure and maintain a 38cm separation between two small gold-platinum blocks.

In the upcoming demonstration, these ‘test masses’ will be allowed to free-fall inside the spacecraft, and a laser system will then attempt to monitor their behaviour, looking for path deviations as small as a few picometres. This is much smaller than the diameter of an atom.

Scaled up, it is like tracking the distance between the tops of London’s Shard skyscraper and New York’s One World Trade Center, and noticing any changes down to just fractions of the width of a human hair.

It is a challenging objective for a space-borne set-up, but it’s the performance an orbiting interferometer will need to achieve if it wants to detect the notoriously weak ripples in space-time produced be even the biggest cosmic cataclysms.

‘The first few days are going to be really boring; we’ll do nothing,’ said McNamara.

‘We’re just going to let these two test masses float free in space and learn something about what we’re seeing, because this type of experiment has never been done before.

‘Then we’ll begin to probe our physics lab. We want to know what can push the test masses out of free-fall.’

LPF cannot itself detect gravitational waves. For that to happen, the 38cm gap between the blocks would need to be a million km or more – something the full Lisa mission aims to do. But the metrology principles can be checked and, most importantly, scientists can begin to characterise the types of ‘noise’ that will inevitably impinge on the experiments.

For LPF, some of these noise sources will be internal to the instrument’s own electronics; then there are physical factors which could work to push the blocks out of their free-fall. The latter might include tiny temperature changes inside the probe, and also the near-imperceptible gravitational tug coming from the mass of the spacecraft itself.

In order to maintain the optimum free-fall environment, LPF must all the while try to fly around the blocks, shielding them from the pressure of sunlight or small micro-meteorite impacts.

To do this job, LPF squirts minute amounts of gas to produce tiny amounts of thrust.

‘The cold-gas thrusters on Lisa Pathfinder will typically be firing with a force that, on Earth, would just about keep a snowflake from falling,’ explains Ralph Cordey from Airbus Defence and Space in the UK, where the probe was assembled.

LPF actually has two separate sets of micro-thrusters with their own control systems. One package has been supplied by European industry; the other comes from America, a contribution to the project from the US space agency NASA.

For the first three months, it will be an all-European show; from late summer onwards, the American controller and thrusters will take over and support the measurements of the laser interferometer.

Once all the testing is complete, LPF will probably run some additional experiments that have nothing to do with gravitational waves.

Ideas under consideration at the moment include trying to detect near-Earth asteroids. This would be done using the spare star-tracker on the probe. The navigation sensor would be programmed to report unexpected movements in its field of view.

Another possibility is to employ the super-sensitive equipment onboard LPF to quantify ‘Big G’, the Gravitational Constant. This fundamental number in Newtonian physics is essential to working out how much gravitational force acts between two masses separated by a known distance.

Big G has been determined very precisely with pendulum devices in labs on Earth. Measuring the Constant with LPF would provide a totally independent assessment.